-

GNU Make & .ONESHELL

If you’re still unfortunate enough to be using GNU Make, the

.ONESHELLspecial target can be quite useful:.ONESHELL: If .ONESHELL is mentioned as a target, then when a target is built all lines of the recipe will be given to a single invocation of the shell rather than each line being invoked separately (see Recipe Execution). -

Under the hood of Bluetooth LE

Under the hood of Bluetooth LE:

A concise, excellent introduction to the workings of the Bluetooth LE protocol. If your introduction to Bluetooth LE was via Apple’s Core Bluetooth framework (which it likely is if you’re an iOS developer), this document explains a lot… especially Core Bluetooth’s “interesting” caching behaviour.

-

Under the hood of Bluetooth LE

Under the hood of Bluetooth LE:

A concise, excellent introduction to the workings of the Bluetooth LE protocol. If your introduction to Bluetooth LE was via Apple’s Core Bluetooth framework (which it likely is if you’re an iOS developer), this document explains a lot… especially Core Bluetooth’s “interesting” caching behaviour.

-

Boost's shared_ptr up to 10× slower than OCaml's garbage collection

Boost’s shared_ptr up to 10× slower than OCaml’s garbage collection:

Modern garbage collector beats reference counting; news at 11. One interesting paragraph:

Note also the new “stack” section that is the first C to beat OCaml, albeit cheating by exploiting the fact that this implementation of this benchmark always happens to allocate and free in FIFO order. So this approach is problem-specific and cannot be used as a general-purpose allocator. However, it is worth noting that the only allocation strategy to beat C also (like OCaml’s nursery) exploits the ability to collect many freed values in constant time by resetting the stack pointer rather than using repeated pops. Therefore, the only allocation strategies likely to approach OCaml’s performance on these kinds of problems are those that exploit sparsity. For example, by manipulating free lists in run-length encoded form.

-

Boost's shared_ptr up to 10× slower than OCaml's garbage collection

Boost’s shared_ptr up to 10× slower than OCaml’s garbage collection:

Modern garbage collector beats reference counting; news at 11. One interesting paragraph:

Note also the new “stack” section that is the first C to beat OCaml, albeit cheating by exploiting the fact that this implementation of this benchmark always happens to allocate and free in FIFO order. So this approach is problem-specific and cannot be used as a general-purpose allocator. However, it is worth noting that the only allocation strategy to beat C also (like OCaml’s nursery) exploits the ability to collect many freed values in constant time by resetting the stack pointer rather than using repeated pops. Therefore, the only allocation strategies likely to approach OCaml’s performance on these kinds of problems are those that exploit sparsity. For example, by manipulating free lists in run-length encoded form.

-

smartscan-mode: Vim's # and * for Emacs

smartscan-mode: Vim’s # and * for Emacs:

“Smart Scan will try to infer the symbol your point is on and let you jump to other, identical, symbols elsewhere in your current buffer with a single key stroke. The advantage over isearch is its unintrusiveness; there are no menus, prompts or other UI elements that require your attention.”

-

smartscan-mode: Vim's # and * for Emacs

smartscan-mode: Vim’s # and * for Emacs:

“Smart Scan will try to infer the symbol your point is on and let you jump to other, identical, symbols elsewhere in your current buffer with a single key stroke. The advantage over isearch is its unintrusiveness; there are no menus, prompts or other UI elements that require your attention.”

-

"I have come around to the view that the real core difficulty of these [distributed] systems is..."

““I have come around to the view that the real core difficulty of these [distributed] systems is operations, not architecture or design. Both are important but good operations can often work around the limitations of bad (or incomplete) software, but good software cannot run reliably with bad operations.””

- Jay Kreps, Getting Real About Distributed System Reliability. -

"I have come around to the view that the real core difficulty of these [distributed] systems is..."

““I have come around to the view that the real core difficulty of these [distributed] systems is operations, not architecture or design. Both are important but good operations can often work around the limitations of bad (or incomplete) software, but good software cannot run reliably with bad operations.””

- Jay Kreps, Getting Real About Distributed System Reliability. -

Add Recently-Run Apps to the Dock

Courtesy of Mac Dev Weekly:

defaults write com.apple.dock \ persistent-others -array-add \ '{ "tile-data" = { "list-type" = 1; }; \ "tile-type" = "recents-tile"; }' \ killall Dock -

Add Recently-Run Apps to the Dock

Courtesy of Mac Dev Weekly:

defaults write com.apple.dock \ persistent-others -array-add \ '{ "tile-data" = { "list-type" = 1; }; \ "tile-type" = "recents-tile"; }' \ killall Dock -

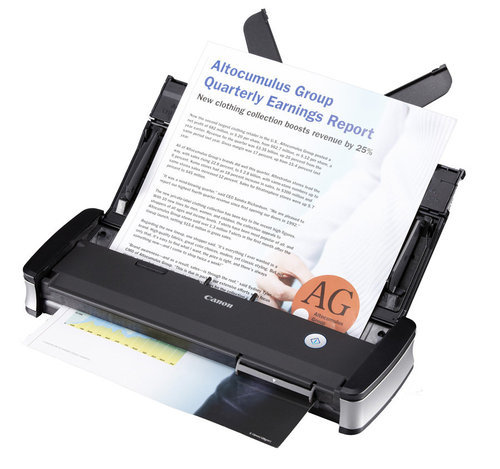

Going Paperless

Going paperless? Get a Canon P-215 ($285) or Canon P-208 ($170), PDFScanner for the Mac ($15), and get going.

We have a great little Swedish-made birch wood filing cabinet that we use to store our paperwork: bank statements, legal documents, that stuff. However, the filing cabinet is almost full (the USA likes paperwork), and I’ve refused to get another one, because more paper means more space and more waste. So, I decided to go paperless: scan everything, store them as PDFs, and shred the paper after it’s scanned.

There are some services (such as Outbox in the USA) that will do this for you. Call me oldskool, but they’re just not my thing: I don’t like the idea of other people reading my mail, any more than I like the idea of other people reading my email. I’d also prefer not to pay a subscription every year, though honestly, at ~$10/month, these services aren’t that expensive if you decide that you really hate doing this yourself. So I decided to see if I could find a solution that did what I wanted:

- scan stuff fast: 5 pages+ per minute, with double-sided (a.k.a. duplex) scanning;

- scan stuff in bulk: at least 10 pages at a time, and save out selected pages to different documents;

- OCR everything: save as text-searchable PDF (searchable by Spotlight on OS X);

- and, the biggest problem with scanners: have software that wasn’t a pain in the arse to use.

Doesn’t seem that onerous, does it? Well, I’ve actually been looking for a solution for a long time now…

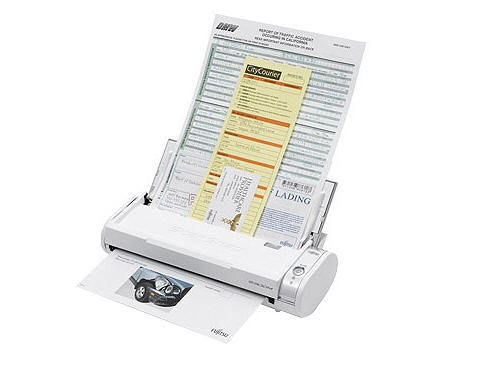

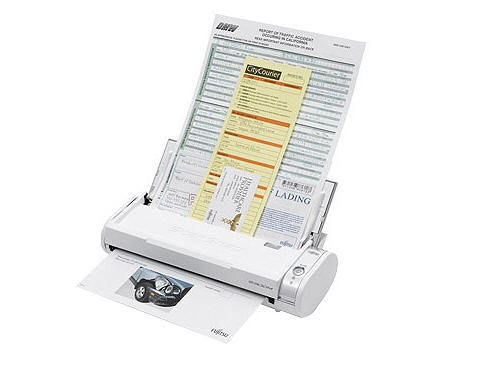

The Fujitsu ScanSnap

I’ve had the legendary Fujitsu ScanSnap S300M for years. The ScanSnap series are the kings of document scanners: duplex, fast, sheet feeder; pick three. Unfortunately, they suffered from one large problem: you had to use Fujitsu’s own software to do the scanning, because they didn’t have TWAIN drivers, which is the standard scanner driver interface on OS X and Windows. This means that on a Mac, you couldn’t use Image Capture, Preview, or Photoshop to scan things, and were limited by what Fujitsu’s software could do. Double unfortunately, Fujitsu’s software is what you’d expect from a company that makes printers and scanners: not great. The more expensive ScanSnaps support OCR, but the S300M didn’t, and I couldn’t cobble together a satisfactory workflow that used the Fujitsu software and integrate it with an OCR program. I tried hacking together Automator scripts, custom AppleScripts, shell and Python stuff, DevonThink Pro Office (which has native support for the ScanSnap) and couldn’t find something satisfactory.

Taking a different route inspired by Linux geekdom, I did try TWAIN SANE for OS X, which takes the hundreds of drivers available for the Linux SANE scanning framework, and presents them as TWAIN devices for OS X. Unfortunately, the driver for the S300M didn’t work:

sane-find-scannerwould find it just once, and never find it again, andscanimagenever worked. I would’ve loved to debug it and fix it, but that “life” thing keeps getting in the way. So, death to all scanners with a proprietary interface. What other options are there?The Canon P-215

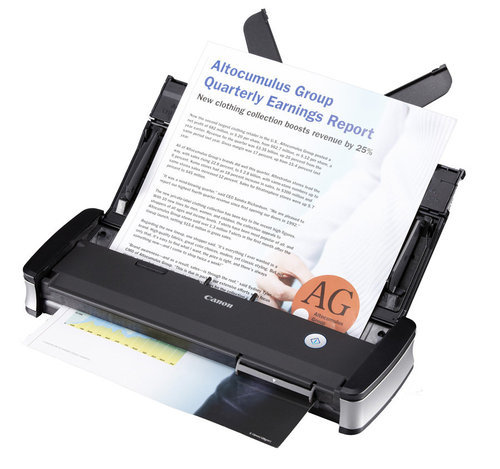

Thankfully, Canon’s entered the market with their very silly-named, yet totally awesome Canon imageFORMULA P-215 Scan-tini Personal Document Scanner. It’s like the Fujitsu ScanSnap S300M, but better in every way. It scans 15ppm instead of the ScanSnap’s 8ppm; has a 20-page sheet feeder instead of 10; can be powered from a single USB port; and most importantly, it’s TWAIN-compliant. The P-215 is $285 on Amazon. The Wirecutter, a fantastic gadget review site, agrees that the P-215 is the most awesomest portable scanner around.

There’s also the Canon P-208 for about $100 less, which is basically the P-215 lite: smaller and slower (about the ScanSnap’s speed), but still TWAIN-complaint. I use the P-215, but see no reason why the P-208 would be significantly worse for what I do. I probably would’ve got the P-208 if it were $170: at the time I bought them, the P-215 was $270 and the P-208 was $230, and I thought the $40 was worth the extra features. $170 is a much better price than $270, though, so look into the P-208 seriously if you’re considering this.

The scanner is designed so that it presents itself as both a scanner and a USB drive when you plug it in, with the USB drive containing the scanning software, so you’re never without it. Clever. The software that comes with the Canon is actually “not that bad” as far as scanning software goes… which still means it’s pretty craptastic. The Wirecutter does a good job of reviewing the software, so I won’t review it here, except that to say that my standards for quality software is probably higher than the Wirecutter’s. However, since the P-215 is TWAIN-compliant, you can use any software you want to scan stuff. So, what’s some good scanning software?

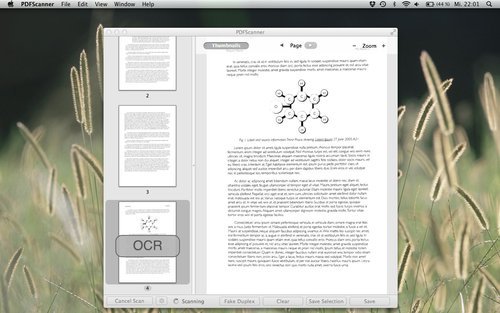

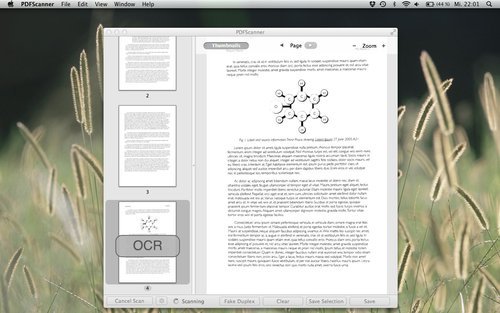

PDFScanner

Thankfully, one coder from Germany was sick of all the crappy scanning software out there, and wrote his Own Damn Scanning Software, creatively named PDFScanner. PDFScanner is just plain excellent. If you have a scanner at all, just go buy it. It’s a measly $15, and I guarantee you that it’s orders of magnitude better than the tosspot scanning software that you got with your scanner.

- It does OCR.

- It does deskewing.

- It detects blank pages and removes them from the scan.

- You can re-order and remove pages that you scanned. (OMG! Wow!)

- It’s multithreaded so it OCRs and deskews multiple pages at once, and puts all those cores in your Mac to work. Oooer.

- It has a “fake duplex” mode, so that if your scanner doesn’t support duplex scanning, you can scan the first side of all your pages, then the second side of all your pages. Cool.

- You can select some pages out of the 20 you scanned, save just those pages as a single PDF, then remove them from the scan. Imagine that.

- You can select different compression levels when saving the PDF.

- It can import existing PDFs and OCR them.

Paired with PDFScanner, the P-215 will quickly munch through your paper documents so that you can happily shred them afterwards. The shredding is satisfying.

Did I mention that PDFScanner is $15? It’s $15. I hope the guy makes 10x as much money from it as the fools who write the retarded scanning software that comes with scanners.

Recommendations

I scan stuff at 300dpi: a one-page document is around 800KB. You may want to scan stuff at higher resolutions if you’re paranoid about reproducing them super-well if you need to re-print them. I don’t think it’s necessary.

I have a folder creatively named “Filing Cabinet” that I throw all my documents into. (Lycaeum is also a cool name if you’re an Ultima geek.) The top-level folder structure inside there mostly resembled the physical filing cabinet: “Banks”, “Cars”, “Healthcare”, etc, and works well. One of the nice things about a digital filing cabinet is that you’re not limited to just one level of dividers: just go create sub-folders inside your top-level folders, e.g. “Insurance” inside “Cars”. (Such advanced technology!) I include the date in the filename for most of my scans in

YYYYMMDDformat, but not all of them (e.g. I do for bank statements and car service appointments, but not for most work-related material).Since all these documents contain some sensitive information, you do want to store them securely, but be able to conveniently access them. I store my stuff on Google Drive since I trust Google’s security (go two-factor authentication).

I expect the virtual filing cabinet to grow to 10-20GB for a few years of data, which is peanuts these days. I’m happy to pay Google the two-digit cost per year to have that much storage space in Google Drive.

Small Niggles

The workflow’s not perfect, but it really is close enough to perfect that I feel it’s about as streamlined as you can get. You do need to double-check that every physical page made it through to the final PDF correctly, which is just common sense. Don’t expect to scan 1000 pages, click Save and shred things without cross-checking.

Feeding in the paper into the Canon P-215 in the orientation that you’d expect means that you have to tell PDFScanner to scan in “Portrait (Upside Down)” mode instead of just “Portrait” mode, which seems a bit odd. (I’d blame this on the Canon TWAIN driver rather than PDFScanner, mind you.) No other side-effects besides having to pick the upside-down orientation, though.

Scanning in a mix of landscape and portrait documents doesn’t work if you want to OCR the whole batch, because PDFScanner will OCR the scan in its original orientation only, and won’t let you re-run OCR after you’ve rotated the page. This just means that you have to scan in portrait documents in one batch, and landscape documents in another batch. Not a big deal, especially since scanning a batch in PDFScanner is simply pressing the “Scan” button. I’ve emailed the PDFScanner author about this, and got a response back within a day saying that he’ll consider adding it to the next version. Maybe it’s already fixed.

It’d be a bonus for the P-215 to be wireless, instead of requiring a USB cable. However, the scanner’s so small and portable that I just grab it, scan stuff, then put it back on the shelf, so this isn’t a problem for me. If you really want, you can buy a fairly expensive $170 WiFi adapter for the P-215. At least you get a battery pack for your $170 too.

The Paperless Workflow In Practice

In practice, the workflow’s worked out quite well. I’m now rapidly churning through the entire filing cabinet’s worth of documents, and have shredded 99% of the paper. The workflow is near-perfect, with the very small caveats mentioned above.

I do keep a few physical documents, such as things printed on special paper (e.g. US social security card), birth certificates, etc. Those exceptions are extremely rare though; in total, I’ve managed to reduce a 80-90cm stack of paper (~3 feet) to about an inch. I love going paperless, and would highly encourage anyone who’s been thinking about it to get a Canon P-208 or P-215, PDFScanner, and make the leap. I said that the shredding is satisfying, right? It’s very satisfying.

-

Going Paperless

Going paperless? Get a Canon P-215 ($285) or Canon P-208 ($170), PDFScanner for the Mac ($15), and get going.

We have a great little Swedish-made birch wood filing cabinet that we use to store our paperwork: bank statements, legal documents, that stuff. However, the filing cabinet is almost full (the USA likes paperwork), and I’ve refused to get another one, because more paper means more space and more waste. So, I decided to go paperless: scan everything, store them as PDFs, and shred the paper after it’s scanned.

There are some services (such as Outbox in the USA) that will do this for you. Call me oldskool, but they’re just not my thing: I don’t like the idea of other people reading my mail, any more than I like the idea of other people reading my email. I’d also prefer not to pay a subscription every year, though honestly, at ~$10/month, these services aren’t that expensive if you decide that you really hate doing this yourself. So I decided to see if I could find a solution that did what I wanted:

- scan stuff fast: 5 pages+ per minute, with double-sided (a.k.a. duplex) scanning;

- scan stuff in bulk: at least 10 pages at a time, and save out selected pages to different documents;

- OCR everything: save as text-searchable PDF (searchable by Spotlight on OS X);

- and, the biggest problem with scanners: have software that wasn’t a pain in the arse to use.

Doesn’t seem that onerous, does it? Well, I’ve actually been looking for a solution for a long time now…

The Fujitsu ScanSnap

I’ve had the legendary Fujitsu ScanSnap S300M for years. The ScanSnap series are the kings of document scanners: duplex, fast, sheet feeder; pick three. Unfortunately, they suffered from one large problem: you had to use Fujitsu’s own software to do the scanning, because they didn’t have TWAIN drivers, which is the standard scanner driver interface on OS X and Windows. This means that on a Mac, you couldn’t use Image Capture, Preview, or Photoshop to scan things, and were limited by what Fujitsu’s software could do. Double unfortunately, Fujitsu’s software is what you’d expect from a company that makes printers and scanners: not great. The more expensive ScanSnaps support OCR, but the S300M didn’t, and I couldn’t cobble together a satisfactory workflow that used the Fujitsu software and integrate it with an OCR program. I tried hacking together Automator scripts, custom AppleScripts, shell and Python stuff, DevonThink Pro Office (which has native support for the ScanSnap) and couldn’t find something satisfactory.

Taking a different route inspired by Linux geekdom, I did try TWAIN SANE for OS X, which takes the hundreds of drivers available for the Linux SANE scanning framework, and presents them as TWAIN devices for OS X. Unfortunately, the driver for the S300M didn’t work:

sane-find-scannerwould find it just once, and never find it again, andscanimagenever worked. I would’ve loved to debug it and fix it, but that “life” thing keeps getting in the way. So, death to all scanners with a proprietary interface. What other options are there?The Canon P-215

Thankfully, Canon’s entered the market with their very silly-named, yet totally awesome Canon imageFORMULA P-215 Scan-tini Personal Document Scanner. It’s like the Fujitsu ScanSnap S300M, but better in every way. It scans 15ppm instead of the ScanSnap’s 8ppm; has a 20-page sheet feeder instead of 10; can be powered from a single USB port; and most importantly, it’s TWAIN-compliant. The P-215 is $285 on Amazon. The Wirecutter, a fantastic gadget review site, agrees that the P-215 is the most awesomest portable scanner around.

There’s also the Canon P-208 for about $100 less, which is basically the P-215 lite: smaller and slower (about the ScanSnap’s speed), but still TWAIN-complaint. I use the P-215, but see no reason why the P-208 would be significantly worse for what I do. I probably would’ve got the P-208 if it were $170: at the time I bought them, the P-215 was $270 and the P-208 was $230, and I thought the $40 was worth the extra features. $170 is a much better price than $270, though, so look into the P-208 seriously if you’re considering this.

The scanner is designed so that it presents itself as both a scanner and a USB drive when you plug it in, with the USB drive containing the scanning software, so you’re never without it. Clever. The software that comes with the Canon is actually “not that bad” as far as scanning software goes… which still means it’s pretty craptastic. The Wirecutter does a good job of reviewing the software, so I won’t review it here, except that to say that my standards for quality software is probably higher than the Wirecutter’s. However, since the P-215 is TWAIN-compliant, you can use any software you want to scan stuff. So, what’s some good scanning software?

PDFScanner

Thankfully, one coder from Germany was sick of all the crappy scanning software out there, and wrote his Own Damn Scanning Software, creatively named PDFScanner. PDFScanner is just plain excellent. If you have a scanner at all, just go buy it. It’s a measly $15, and I guarantee you that it’s orders of magnitude better than the tosspot scanning software that you got with your scanner.

- It does OCR.

- It does deskewing.

- It detects blank pages and removes them from the scan.

- You can re-order and remove pages that you scanned. (OMG! Wow!)

- It’s multithreaded so it OCRs and deskews multiple pages at once, and puts all those cores in your Mac to work. Oooer.

- It has a “fake duplex” mode, so that if your scanner doesn’t support duplex scanning, you can scan the first side of all your pages, then the second side of all your pages. Cool.

- You can select some pages out of the 20 you scanned, save just those pages as a single PDF, then remove them from the scan. Imagine that.

- You can select different compression levels when saving the PDF.

- It can import existing PDFs and OCR them.

Paired with PDFScanner, the P-215 will quickly munch through your paper documents so that you can happily shred them afterwards. The shredding is satisfying.

Did I mention that PDFScanner is $15? It’s $15. I hope the guy makes 10x as much money from it as the fools who write the retarded scanning software that comes with scanners.

Recommendations

I scan stuff at 300dpi: a one-page document is around 800KB. You may want to scan stuff at higher resolutions if you’re paranoid about reproducing them super-well if you need to re-print them. I don’t think it’s necessary.

I have a folder creatively named “Filing Cabinet” that I throw all my documents into. (Lycaeum is also a cool name if you’re an Ultima geek.) The top-level folder structure inside there mostly resembled the physical filing cabinet: “Banks”, “Cars”, “Healthcare”, etc, and works well. One of the nice things about a digital filing cabinet is that you’re not limited to just one level of dividers: just go create sub-folders inside your top-level folders, e.g. “Insurance” inside “Cars”. (Such advanced technology!) I include the date in the filename for most of my scans in

YYYYMMDDformat, but not all of them (e.g. I do for bank statements and car service appointments, but not for most work-related material).Since all these documents contain some sensitive information, you do want to store them securely, but be able to conveniently access them. I store my stuff on Google Drive since I trust Google’s security (go two-factor authentication).

I expect the virtual filing cabinet to grow to 10-20GB for a few years of data, which is peanuts these days. I’m happy to pay Google the two-digit cost per year to have that much storage space in Google Drive.

Small Niggles

The workflow’s not perfect, but it really is close enough to perfect that I feel it’s about as streamlined as you can get. You do need to double-check that every physical page made it through to the final PDF correctly, which is just common sense. Don’t expect to scan 1000 pages, click Save and shred things without cross-checking.

Feeding in the paper into the Canon P-215 in the orientation that you’d expect means that you have to tell PDFScanner to scan in “Portrait (Upside Down)” mode instead of just “Portrait” mode, which seems a bit odd. (I’d blame this on the Canon TWAIN driver rather than PDFScanner, mind you.) No other side-effects besides having to pick the upside-down orientation, though.

Scanning in a mix of landscape and portrait documents doesn’t work if you want to OCR the whole batch, because PDFScanner will OCR the scan in its original orientation only, and won’t let you re-run OCR after you’ve rotated the page. This just means that you have to scan in portrait documents in one batch, and landscape documents in another batch. Not a big deal, especially since scanning a batch in PDFScanner is simply pressing the “Scan” button. I’ve emailed the PDFScanner author about this, and got a response back within a day saying that he’ll consider adding it to the next version. Maybe it’s already fixed.

It’d be a bonus for the P-215 to be wireless, instead of requiring a USB cable. However, the scanner’s so small and portable that I just grab it, scan stuff, then put it back on the shelf, so this isn’t a problem for me. If you really want, you can buy a fairly expensive $170 WiFi adapter for the P-215. At least you get a battery pack for your $170 too.

The Paperless Workflow In Practice

In practice, the workflow’s worked out quite well. I’m now rapidly churning through the entire filing cabinet’s worth of documents, and have shredded 99% of the paper. The workflow is near-perfect, with the very small caveats mentioned above.

I do keep a few physical documents, such as things printed on special paper (e.g. US social security card), birth certificates, etc. Those exceptions are extremely rare though; in total, I’ve managed to reduce a 80-90cm stack of paper (~3 feet) to about an inch. I love going paperless, and would highly encourage anyone who’s been thinking about it to get a Canon P-208 or P-215, PDFScanner, and make the leap. I said that the shredding is satisfying, right? It’s very satisfying.

-

Two new mixes

I’ve been pretty dormant in my music for the past few years, but I have been working on two two mixes in my sparse spare time: Tes Lyric, a weird blend of electronica, classical and rock, and Stage Superior, a progressive house mix. They’re up on my music page now; enjoy!

-

Two new mixes

I’ve been pretty dormant in my music for the past few years, but I have been working on two two mixes in my sparse spare time: Tes Lyric, a weird blend of electronica, classical and rock, and Stage Superior, a progressive house mix. They’re up on my music page now; enjoy!

-

Immutability and Blocks, Lambdas and Closures [UPDATE x2]

I recently ran into some “interesting” behaviour when using

lambdain Python. Perhaps it’s only interesting because I learnt lambdas from a functional language background, where I expect that they work a particular way, and the rest of the world that learnt lambdas through Python, Ruby or JavaScript disagree. (Shouts out to you Objective-C developers who are discovering the wonders of blocks, too.) Nevertheless, I thought this would be blog-worthy. Here’s some Python code that shows the behaviour that I found on Stack Overflow:Since I succumb to reading source code in blog posts by interpreting them as “blah”1, a high-level overview of what that code does is:

- iterate over a list of strings,

- create a new list of functions that prints out the strings, and then

- call those functions, which prints the strings.

Simple, eh? Prints “do”, then “re”, then “mi”, eh? Wrong. It prints out “mi”, then “mi”, then “mi”. Ka-what?

(I’d like to stress that this isn’t a theoretical example. I hit this problem in production code, and boy, it was lots of fun to debug. I hit the solution right away thanks to the wonders of Google and Stack Overflow, but it took me a long time to figure out that something was going wrong at that particular point in the code, and not somewhere else in my logic.)

The second answer to the Stack Overflow question is the clearest exposition of the problem, with a rather clever solution too. I won’t repeat it here since you all know how to follow links. However, while that answer explains the problem, there’s a deeper issue. The inconceivable Manuel Chakravarty provides a far more insightful answer when I emailed him to express my surprise at Python’s lambda semantics:

This is a very awkward semantics for lambdas. It is also probably almost impossible to have a reasonable semantics for lambdas in a language, such as Python.

The behaviour that the person on SO, and I guess you, found surprising is that the contents of the free variables of the lambdas body could change between the point in time where the closure for the lambda was created and when that closure was finally executed. The obvious solution is to put a copy of the value of the variable (instead of a pointer to the original variable) into the closure.

But how about a lambda where a free variable refers to a 100MB object graph? Do you want that to be deep copied by default? If not, you can get the same problem again.

So, the real issue here is the interaction between mutable storage and closures. Sometimes you want the free variables to be copied (so you get their value at closure creation time) and sometimes you don’t want them copied (so you get their value at closure execution time or simply because the value is big and you don’t want to copy it).

And, indeed, since I love being categorised as a massive Apple fanboy, I found the same surprising behaviour with Apple’s blocks semantics in C, too:

You can see the Gist page for this sample code to see how to work around the problem in Objective-C (basically: copy the block), and also to see what it’d look like in Haskell (with the correct behaviour).

In Python, the Stack Overflow solution that I linked to has an extremely concise way of giving the programmer the option to either copy the value or simply maintain a reference to it, and the syntax is clear enough—once you understand what on Earth what the problem is, that is. I don’t understand Ruby or JavaScript well enough to comment on how they’d capture the immediate value for lambdas or whether they considered this design problem. C++0x will, unsurprisingly, give programmers full control over lambda behaviour that will no doubt confuse the hell out of people. (See the C++0x language draft, section 5.1.2 on page 91.)

In his usual incredibly didactic manner, Manuel then went on to explain something else insightful:

I believe there is a deeper issue here. Copying features of FP languages is the hip thing in language design these days. That’s fine, but many of the high-powered FP language features derive their convenience from being unspecific, or at least unconventional, about the execution time of a piece of code. Lambdas delay code execution, laziness provides demand-dependent code execution plus memoisation, continuations capture closures including their environment (ie, the stack), etc. Another instance of that problem was highlighted by Joe Duffy in his STM retrospective.

I would say, mutability and flexible control flow are fundamentally at odds in language design.

Indeed, I’ve been doing some language exploration again lately as the lack of static typing in Python is really beginning to bug me, and almost all the modern languages that attempt to pull functional programming concepts into object-oriented land seem like a complete Frankenstein, partially due to mutability. Language designers, please, this is 2011: multicore computing is the norm now, whether we like it or not. If you’re going to make an imperative language—and that includes all your OO languages—I’ll paraphrase Tim Sweeney: in a concurrent world, mutable is the wrong default! I’d love a C++ or Objective-C where all variables are

constby default.One take-away point from all this is to try to keep your language semantics simple. I love Dan Ingall’s quote from Design Principles Behind Smalltalk: “if a system is to serve the creative spirit, it must be entirely comprehensible to a single individual”. I love Objective-C partially because its message-passing semantics are straightforward, and its runtime has a amazingly compact API and implementation considering how powerful it is. I’ve been using Python for a while now, and I still don’t really know the truly nitty-gritty details about subtle object behaviours (e.g. class variables, multiple inheritance). And I mostly agree with Guido’s assertion that Python should not have included lambda nor reduce, given what Python’s goals are. After discovering this quirk about them, I’m still using the lambda in production code because the code savings does justify the complexity, but you bet your ass there’s a big comment there saying “warning, pretentous code trickery be here!”

1. See point 13 of Knuth et al.’s Mathematical Writing report.

UPDATE: There’s a lot more subtlety at play here than I first realised, and a couple of statements I’ve made above are incorrect. Please see the comments if you want to really figure out what’s going on: I’d summarise the issues, but the interaction between various language semantics are extremely subtle and I fear I’d simply get it wrong again. Thank you to all the commenters for both correcting me and adding a lot of value to this post. (I like this Internet thing! Other people do my work for me!)

Update #2

I’ve been overwhelmed by the comments, in both the workload sense and in the pleasantly-surprised-that-this-provoked-some-discussion sense. Boy, did I get skooled in a couple of areas. I’ve had a couple of requests to try to summarise the issues here, so I’ll do my best to do so.

Retrospective: Python

It’s clear that my misunderstanding of Python’s scoping/namespace rules is the underlying cause of the problem: in Python, variables declared in

for/while/ifstatements will be declared in the compound block’s existing scope, and not create a new scope. So in my example above, using alambdainside the for loop creates a closure that references the variablem, butm’s value has changed by the end of the for loop to “mi”, which is why it prints “mi, mi, mi”. I’d prefer to link to the official Python documentation about this here rather than writing my own words that may be incorrect, but I can’t actually find anything in the official documentation that authoritatively defines this. I can find a lot of blog posts warning about it—just Google for “Python for while if scoping” to see a few—and I’ve perused the entire chapter on Python’s compound statements, but I just can’t find it. Please let me know in the comments if you do find a link, in which case I’ll retract half this paragraph and stand corrected, and also a little shorter.I stand by my assertion that Python’s

for/while/ifscoping is slightly surprising, and for some particular scenarios—like this—it can cause some problems that are very difficult to debug. You may call me a dumbass for bringing assumptions about one language to another, and I will accept my dumbassery award. I will happily admit that this semantics has advantages, such as being able to access the last value assigned in aforloop, or not requiring definitions of variables before executing anifstatement that assigns to those variables and using it later in the same scope. All language design decisions have advantages and disadvantages, and I respect Python’s choice here. However, I’ve been using Python for a few years, consider myself to be at least a somewhat competent programmer, and only just found out about this behaviour. I’m surprised 90% of my code actually works as intended given these semantics. In my defence, this behaviour was not mentioned at all in the excellent Python tutorials, and, as mentioned above, I can’t a reference for it in the official Python documentation. I’d expect that this behaviour is enough of a difference vs other languages to at least be mentioned. You may disagree with me and regard this as a minor issue that only shows up when you do crazy foo like uselambdainside aforloop, in which case I’ll shrug my shoulders and go drink another beer.I’d be interested to see if anyone can come up an equivalent for the “Closures and lexical closures” example at http://c2.com/cgi/wiki?ScopeAndClosures, given another Python scoping rule that assignment to a variable automatically makes it a local variable. (Thus, the necessity for Python’s

globalkeyword.) I’m guessing that you can create thecreateAdderclosure example there with Python’s lambdas, but my brain is pretty bugged out today so I can’t find an equivalent for it right now. You can simply write a callable class to do that and instantiate an object, of course, which I do think is about 1000x clearer. There’s no point using closures when the culture understands objects a ton better, and the resulting code is more maintainable.Python summary: understand how scoping in

for/while/ifblocks work, otherwise you’ll run into problems that can cost you hours, and get skooled publicly on the Internet for all your comrades to laugh at. Even with all the language design decisions that I consider weird, I still respect and like Python, and I feel that Guido’s answer to the stuff I was attempting would be “don’t do that”. Writing a callable class in Python is far less tricky than using closures, because a billion times more people understand their semantics. It’s always a design question of whether the extra trickiness is more maintainable or not.Retrospective: Blocks in C

My C code with blocks failed for a completely different reason unrelated to the Python version, and this was a total beginner’s error with blocks, for which I’m slightly embarrassed. The block was being stack-allocated, so upon exit of the

forloop that assigns the function list, the pointers to the blocks are effectively invalid. I was a little unlucky that the program didn’t crash. The correct solution is to perform aBlock_copy, in which case things work as expected.Retrospective: Closures

Not all closures are the same; or, rather, closures are closures, but their semantics can differ from language to language due to many different language design decisions—such as how one chooses to define the lexical environment. Wikipedia’s article on closures has an excellent section on differences in closure semantics.

Retrospective: Mutability

I stand by all my assertions about mutability. This is where the Haskell tribe will nod their collective heads, and all the anti-Haskell tribes think I’m an idiot. Look, I use a lot of languages, and I love and hate many things about each of them, Haskell included. I fought against Haskell for years and hated it until I finally realised that one of its massive benefits is that things bloody well work an unbelievable amount of the time once your code compiles. Don’t underestimate how much of a revelation this is, because that’s the point where the language’s beauty, elegance and crazy type system fade into the background and, for the first time, you see one gigantic pragmatic advantage of Haskell.

One of the things that Haskell does to achieve this is the severe restriction on making things immutable. Apart from the lovely checkbox reason that you can write concurrent-safe algorithms with far less fear, I truly believe that this makes for generally more maintainable code. You can read code and think once about what value a variable holds, rather than keep it in the back of your mind all the time. The human mind is better at keeping track of multiple names, rather than a single name with different states.

The interaction of state and control flow is perhaps the most complex thing to reason about in programming—think concurrency, re-entrancy, disruptive control flow such as

longjmp, exceptions, co-routines—and mutability complicates that by an order of magnitude. The subtle difference in behaviour between all the languages discussed in the comments is exemplar that “well-understood” concepts such as lexical scoping,forloops and closures can produce a result that many people still don’t expect; at least for this simple example, these issues would have been avoided altogether if mutability was disallowed. Of course mutability has its place. I’m just advocating that we should restrict it where possible, and at least a smattering of other languages—and hopefully everyone who has to deal with thread-safe code—agrees with me.Closing

I’d truly like to thank everyone who added their voice and spent the time to comment on this post. It’s been highly enlightening, humbling, and has renewed my interest in discussing programming languages again after a long time away from it. And hey, I’m blogging again. (Though perhaps after this post, you may not think that two of those things are good things.) It’s always nice when you learn something new, which I wouldn’t have if not for the excellent peer review. Science: it works, bitches!

-

Immutability and Blocks, Lambdas and Closures [UPDATE x2]

I recently ran into some “interesting” behaviour when using

lambdain Python. Perhaps it’s only interesting because I learnt lambdas from a functional language background, where I expect that they work a particular way, and the rest of the world that learnt lambdas through Python, Ruby or JavaScript disagree. (Shouts out to you Objective-C developers who are discovering the wonders of blocks, too.) Nevertheless, I thought this would be blog-worthy. Here’s some Python code that shows the behaviour that I found on Stack Overflow:Since I succumb to reading source code in blog posts by interpreting them as “blah”1, a high-level overview of what that code does is:

- iterate over a list of strings,

- create a new list of functions that prints out the strings, and then

- call those functions, which prints the strings.

Simple, eh? Prints “do”, then “re”, then “mi”, eh? Wrong. It prints out “mi”, then “mi”, then “mi”. Ka-what?

(I’d like to stress that this isn’t a theoretical example. I hit this problem in production code, and boy, it was lots of fun to debug. I hit the solution right away thanks to the wonders of Google and Stack Overflow, but it took me a long time to figure out that something was going wrong at that particular point in the code, and not somewhere else in my logic.)

The second answer to the Stack Overflow question is the clearest exposition of the problem, with a rather clever solution too. I won’t repeat it here since you all know how to follow links. However, while that answer explains the problem, there’s a deeper issue. The inconceivable Manuel Chakravarty provides a far more insightful answer when I emailed him to express my surprise at Python’s lambda semantics:

This is a very awkward semantics for lambdas. It is also probably almost impossible to have a reasonable semantics for lambdas in a language, such as Python.

The behaviour that the person on SO, and I guess you, found surprising is that the contents of the free variables of the lambdas body could change between the point in time where the closure for the lambda was created and when that closure was finally executed. The obvious solution is to put a copy of the value of the variable (instead of a pointer to the original variable) into the closure.

But how about a lambda where a free variable refers to a 100MB object graph? Do you want that to be deep copied by default? If not, you can get the same problem again.

So, the real issue here is the interaction between mutable storage and closures. Sometimes you want the free variables to be copied (so you get their value at closure creation time) and sometimes you don’t want them copied (so you get their value at closure execution time or simply because the value is big and you don’t want to copy it).

And, indeed, since I love being categorised as a massive Apple fanboy, I found the same surprising behaviour with Apple’s blocks semantics in C, too:

You can see the Gist page for this sample code to see how to work around the problem in Objective-C (basically: copy the block), and also to see what it’d look like in Haskell (with the correct behaviour).

In Python, the Stack Overflow solution that I linked to has an extremely concise way of giving the programmer the option to either copy the value or simply maintain a reference to it, and the syntax is clear enough—once you understand what on Earth what the problem is, that is. I don’t understand Ruby or JavaScript well enough to comment on how they’d capture the immediate value for lambdas or whether they considered this design problem. C++0x will, unsurprisingly, give programmers full control over lambda behaviour that will no doubt confuse the hell out of people. (See the C++0x language draft, section 5.1.2 on page 91.)

In his usual incredibly didactic manner, Manuel then went on to explain something else insightful:

I believe there is a deeper issue here. Copying features of FP languages is the hip thing in language design these days. That’s fine, but many of the high-powered FP language features derive their convenience from being unspecific, or at least unconventional, about the execution time of a piece of code. Lambdas delay code execution, laziness provides demand-dependent code execution plus memoisation, continuations capture closures including their environment (ie, the stack), etc. Another instance of that problem was highlighted by Joe Duffy in his STM retrospective.

I would say, mutability and flexible control flow are fundamentally at odds in language design.

Indeed, I’ve been doing some language exploration again lately as the lack of static typing in Python is really beginning to bug me, and almost all the modern languages that attempt to pull functional programming concepts into object-oriented land seem like a complete Frankenstein, partially due to mutability. Language designers, please, this is 2011: multicore computing is the norm now, whether we like it or not. If you’re going to make an imperative language—and that includes all your OO languages—I’ll paraphrase Tim Sweeney: in a concurrent world, mutable is the wrong default! I’d love a C++ or Objective-C where all variables are

constby default.One take-away point from all this is to try to keep your language semantics simple. I love Dan Ingall’s quote from Design Principles Behind Smalltalk: “if a system is to serve the creative spirit, it must be entirely comprehensible to a single individual”. I love Objective-C partially because its message-passing semantics are straightforward, and its runtime has a amazingly compact API and implementation considering how powerful it is. I’ve been using Python for a while now, and I still don’t really know the truly nitty-gritty details about subtle object behaviours (e.g. class variables, multiple inheritance). And I mostly agree with Guido’s assertion that Python should not have included lambda nor reduce, given what Python’s goals are. After discovering this quirk about them, I’m still using the lambda in production code because the code savings does justify the complexity, but you bet your ass there’s a big comment there saying “warning, pretentous code trickery be here!”

1. See point 13 of Knuth et al.’s Mathematical Writing report.

UPDATE: There’s a lot more subtlety at play here than I first realised, and a couple of statements I’ve made above are incorrect. Please see the comments if you want to really figure out what’s going on: I’d summarise the issues, but the interaction between various language semantics are extremely subtle and I fear I’d simply get it wrong again. Thank you to all the commenters for both correcting me and adding a lot of value to this post. (I like this Internet thing! Other people do my work for me!)

Update #2

I’ve been overwhelmed by the comments, in both the workload sense and in the pleasantly-surprised-that-this-provoked-some-discussion sense. Boy, did I get skooled in a couple of areas. I’ve had a couple of requests to try to summarise the issues here, so I’ll do my best to do so.

Retrospective: Python

It’s clear that my misunderstanding of Python’s scoping/namespace rules is the underlying cause of the problem: in Python, variables declared in

for/while/ifstatements will be declared in the compound block’s existing scope, and not create a new scope. So in my example above, using alambdainside the for loop creates a closure that references the variablem, butm’s value has changed by the end of the for loop to “mi”, which is why it prints “mi, mi, mi”. I’d prefer to link to the official Python documentation about this here rather than writing my own words that may be incorrect, but I can’t actually find anything in the official documentation that authoritatively defines this. I can find a lot of blog posts warning about it—just Google for “Python for while if scoping” to see a few—and I’ve perused the entire chapter on Python’s compound statements, but I just can’t find it. Please let me know in the comments if you do find a link, in which case I’ll retract half this paragraph and stand corrected, and also a little shorter.I stand by my assertion that Python’s

for/while/ifscoping is slightly surprising, and for some particular scenarios—like this—it can cause some problems that are very difficult to debug. You may call me a dumbass for bringing assumptions about one language to another, and I will accept my dumbassery award. I will happily admit that this semantics has advantages, such as being able to access the last value assigned in aforloop, or not requiring definitions of variables before executing anifstatement that assigns to those variables and using it later in the same scope. All language design decisions have advantages and disadvantages, and I respect Python’s choice here. However, I’ve been using Python for a few years, consider myself to be at least a somewhat competent programmer, and only just found out about this behaviour. I’m surprised 90% of my code actually works as intended given these semantics. In my defence, this behaviour was not mentioned at all in the excellent Python tutorials, and, as mentioned above, I can’t a reference for it in the official Python documentation. I’d expect that this behaviour is enough of a difference vs other languages to at least be mentioned. You may disagree with me and regard this as a minor issue that only shows up when you do crazy foo like uselambdainside aforloop, in which case I’ll shrug my shoulders and go drink another beer.I’d be interested to see if anyone can come up an equivalent for the “Closures and lexical closures” example at http://c2.com/cgi/wiki?ScopeAndClosures, given another Python scoping rule that assignment to a variable automatically makes it a local variable. (Thus, the necessity for Python’s

globalkeyword.) I’m guessing that you can create thecreateAdderclosure example there with Python’s lambdas, but my brain is pretty bugged out today so I can’t find an equivalent for it right now. You can simply write a callable class to do that and instantiate an object, of course, which I do think is about 1000x clearer. There’s no point using closures when the culture understands objects a ton better, and the resulting code is more maintainable.Python summary: understand how scoping in

for/while/ifblocks work, otherwise you’ll run into problems that can cost you hours, and get skooled publicly on the Internet for all your comrades to laugh at. Even with all the language design decisions that I consider weird, I still respect and like Python, and I feel that Guido’s answer to the stuff I was attempting would be “don’t do that”. Writing a callable class in Python is far less tricky than using closures, because a billion times more people understand their semantics. It’s always a design question of whether the extra trickiness is more maintainable or not.Retrospective: Blocks in C

My C code with blocks failed for a completely different reason unrelated to the Python version, and this was a total beginner’s error with blocks, for which I’m slightly embarrassed. The block was being stack-allocated, so upon exit of the

forloop that assigns the function list, the pointers to the blocks are effectively invalid. I was a little unlucky that the program didn’t crash. The correct solution is to perform aBlock_copy, in which case things work as expected.Retrospective: Closures

Not all closures are the same; or, rather, closures are closures, but their semantics can differ from language to language due to many different language design decisions—such as how one chooses to define the lexical environment. Wikipedia’s article on closures has an excellent section on differences in closure semantics.

Retrospective: Mutability

I stand by all my assertions about mutability. This is where the Haskell tribe will nod their collective heads, and all the anti-Haskell tribes think I’m an idiot. Look, I use a lot of languages, and I love and hate many things about each of them, Haskell included. I fought against Haskell for years and hated it until I finally realised that one of its massive benefits is that things bloody well work an unbelievable amount of the time once your code compiles. Don’t underestimate how much of a revelation this is, because that’s the point where the language’s beauty, elegance and crazy type system fade into the background and, for the first time, you see one gigantic pragmatic advantage of Haskell.

One of the things that Haskell does to achieve this is the severe restriction on making things immutable. Apart from the lovely checkbox reason that you can write concurrent-safe algorithms with far less fear, I truly believe that this makes for generally more maintainable code. You can read code and think once about what value a variable holds, rather than keep it in the back of your mind all the time. The human mind is better at keeping track of multiple names, rather than a single name with different states.

The interaction of state and control flow is perhaps the most complex thing to reason about in programming—think concurrency, re-entrancy, disruptive control flow such as

longjmp, exceptions, co-routines—and mutability complicates that by an order of magnitude. The subtle difference in behaviour between all the languages discussed in the comments is exemplar that “well-understood” concepts such as lexical scoping,forloops and closures can produce a result that many people still don’t expect; at least for this simple example, these issues would have been avoided altogether if mutability was disallowed. Of course mutability has its place. I’m just advocating that we should restrict it where possible, and at least a smattering of other languages—and hopefully everyone who has to deal with thread-safe code—agrees with me.Closing

I’d truly like to thank everyone who added their voice and spent the time to comment on this post. It’s been highly enlightening, humbling, and has renewed my interest in discussing programming languages again after a long time away from it. And hey, I’m blogging again. (Though perhaps after this post, you may not think that two of those things are good things.) It’s always nice when you learn something new, which I wouldn’t have if not for the excellent peer review. Science: it works, bitches!

-

The Projectionist

There comes in the career of every motion picture that final occasion when all the artistry, all the earnest constructive endeavor of all the man-power and genius of the industry, and all the capital investment, too, must pour through the narrow gate of the projector on its way to the fulfilment of its purpose, the final delivery to the public.

The delivery is a constant miracle of men and mechanism in the projection rooms of the world’s fifty thousand theatres. That narrow ribbon, thirty-five millimetres, flowing at twenty-four frames a second through the scintillating blaze of the spot at the picture aperture and coursing by at an exactingly-precise 90 feet a minute past the light slit of the sound system, demands a quality of skill and faithful, unfailing attention upon which the whole great industry depends.

The projector lens is the neck in the bottle through which all must pass. The projectionist presiding over that mechanism is responsible for the ultimate performance upon which we must all depend.

The projector must not fail, and more importantly still, the man must not fail or permit it to waiver in its performance. It is to the tremendous credit of the skill of the modern projectionist that perfect presentation of the motion picture upon the screen is today a commonplace, a perfection that is taken as a matter of course.

Adolph Zukor, Chairman of Paramount Pictures, 1935. It still applies as much today as it did back then.

-

The Projectionist

There comes in the career of every motion picture that final occasion when all the artistry, all the earnest constructive endeavor of all the man-power and genius of the industry, and all the capital investment, too, must pour through the narrow gate of the projector on its way to the fulfilment of its purpose, the final delivery to the public.

The delivery is a constant miracle of men and mechanism in the projection rooms of the world’s fifty thousand theatres. That narrow ribbon, thirty-five millimetres, flowing at twenty-four frames a second through the scintillating blaze of the spot at the picture aperture and coursing by at an exactingly-precise 90 feet a minute past the light slit of the sound system, demands a quality of skill and faithful, unfailing attention upon which the whole great industry depends.

The projector lens is the neck in the bottle through which all must pass. The projectionist presiding over that mechanism is responsible for the ultimate performance upon which we must all depend.

The projector must not fail, and more importantly still, the man must not fail or permit it to waiver in its performance. It is to the tremendous credit of the skill of the modern projectionist that perfect presentation of the motion picture upon the screen is today a commonplace, a perfection that is taken as a matter of course.

Adolph Zukor, Chairman of Paramount Pictures, 1935. It still applies as much today as it did back then.

-

It Gets Better

Pixar’s latest short film. I’m so proud and honoured to be working with such an amazing group of people.